How we’re failing at patient education for monkeypox

Medical Pharmaceutical Translations • Aug 8, 2022 12:00:00 AM

Last week, the US government declared monkeypox a national public health emergency. With more than 7,000 cases in the US and more than 28,000 worldwide, it’s time for awareness and prevention to go into high gear. But is it too late?

Despite all of the talk about monkeypox, many people are in the dark about what this condition really is, how it spreads, and what we can do to prevent even more cases.

A major reason behind this lack of information is that while we’ve known about the monkeypox virus since the 1950’s, it’s presenting very differently this time around. Many of the characteristics of this strain has lead to the media often portraying it as a sexually transmitted infection (STI).

Although monkeypox usually affects children, this particular outbreak is primarily affecting gay and bisexual men, who currently make up 95-99% of known cases in the US. And although lesions are usually found on various parts of the body, in this new strain lesions often appear only in the genital or anal area.

Monkeypox is spread by close contact with someone who has lesions, and is possibly also transmitted through close and prolonged exposure to someone’s saliva, including in the air. It may also be transmitted by bodily fluids.

For all of these reasons, it’s understandable that the condition has been confused or conflated with an STI. And it’s important to focus on warning sexually active gay and bisexual men about it. But only focusing on this community, as well as closely associating monkeypox with sexual activity, is dangerous.

For one thing, as numerous experts have pointed out, it makes the rest of the population think they’re not at risk. In reality, anyone can get monkeypox, and cases are increasingly being reported in other groups, including children and, recently, a pregnant woman in the US.

Labeling a condition an STI associates it with shame, which means people may be reluctant to come forward when they have symptoms, or even to get tested. Add to this monkeypox’s association with the LGBTQ+ community; as Professor Paul Hunter points out, a person taking action like isolating because they have monkeypox could be considered “tantamount to coming out”.

This could not only lead to people not admitting they have the virus - they may also not want to reveal the people they’ve been in contact with, for fear of outing them, an issue that could be as serious as life or death in countries where sexual relations between people of the same sex is illegal.

For all the press this virus is getting, few articles share or link to concrete, basic information about transmission, which has lead to fear and speculation about everything from touching doorknobs to whether or not the virus can live in drinking water.

Another crucial flaw in patient information around monkeypox regards the vaccine. According to a survey by Annenberg Public Policy Center, 66% of Americans either aren’t sure there’s a vaccine for monekypox, or outright don’t believe one exists. But there are actually two vaccination options

that can prevent a monkeypox infection or in some cases reduce symptoms if it’s administered at the right time.

Unfortunately, on top of lack of information, an additional problem with the monkeypox vaccines is that there aren’t enough available for everyone.

The shortage of vaccines has been widely covered by the media, but another troubling issue hasn’t: Monkeypox can spread to animals. An infected person should avoid contact with animals in order to limit the spread. Otherwise, this condition could have devastating consequences for multiple species, and continue to spread back to humans, as well.

Yet another monkeypox communication problem regards masks. In order to share accurate information and avoid panic, the public is being told that monkeypox isn’t as contagious or easily transmitted through airborne contact as Covid-19. Nevertheless, it can be transmitted by moisture and respiration when in a closed space with someone for a prolonged period of time. Infected people need to wear a mask around anyone they have prolonged contact with, including caretakers and family members - but many may not be aware of this.

It’s not just the general public who are confused about monkeypox. Many healthcare workers have difficulty diagnosing it, since it isn’t presenting in the typical way. Early symptoms mirror those of Covid, and later symptoms often present similarly to STIs like herpes, vastly increasing the possibility of confusion and false diagnoses.

Testing is also difficult, requiring a very good swab sample from a lesion. Some patients who complain of symptoms may not have lesions yet.

Add to all of these challenges a lack of funding for sexual health clinics, where many people in the LGBTQ+ community feel safest when it comes to getting tested, and you have a situation that’s becoming overwhelming, with a lack of testing materials and vaccines.

Some experts think it’s too late to stop the monkeypox outbreak from possibly growing to pandemic levels. But others believe there may still be hope.

Echoing many experts, Dr. Tyler TerMeer of the San Francisco AIDS Foundation stresses that patient information needs to be tailored to specific communities and events. Pamphlets and other materials could be distributed at events targeted towards the LGBTQ+ community, for instance, and the tone of these materials needs to be sex positive and approachable. Materials could also be adapted for parents, since there’s growing concern that the start of the school year will mean more children will be exposed to - and spread - monkeypox.

When it comes to this current monkeypox outbreak, few things are certain. But with the limited number of vaccines and lack of awareness, one thing is for sure: patient materials are a crucial weapon in our fight against it.

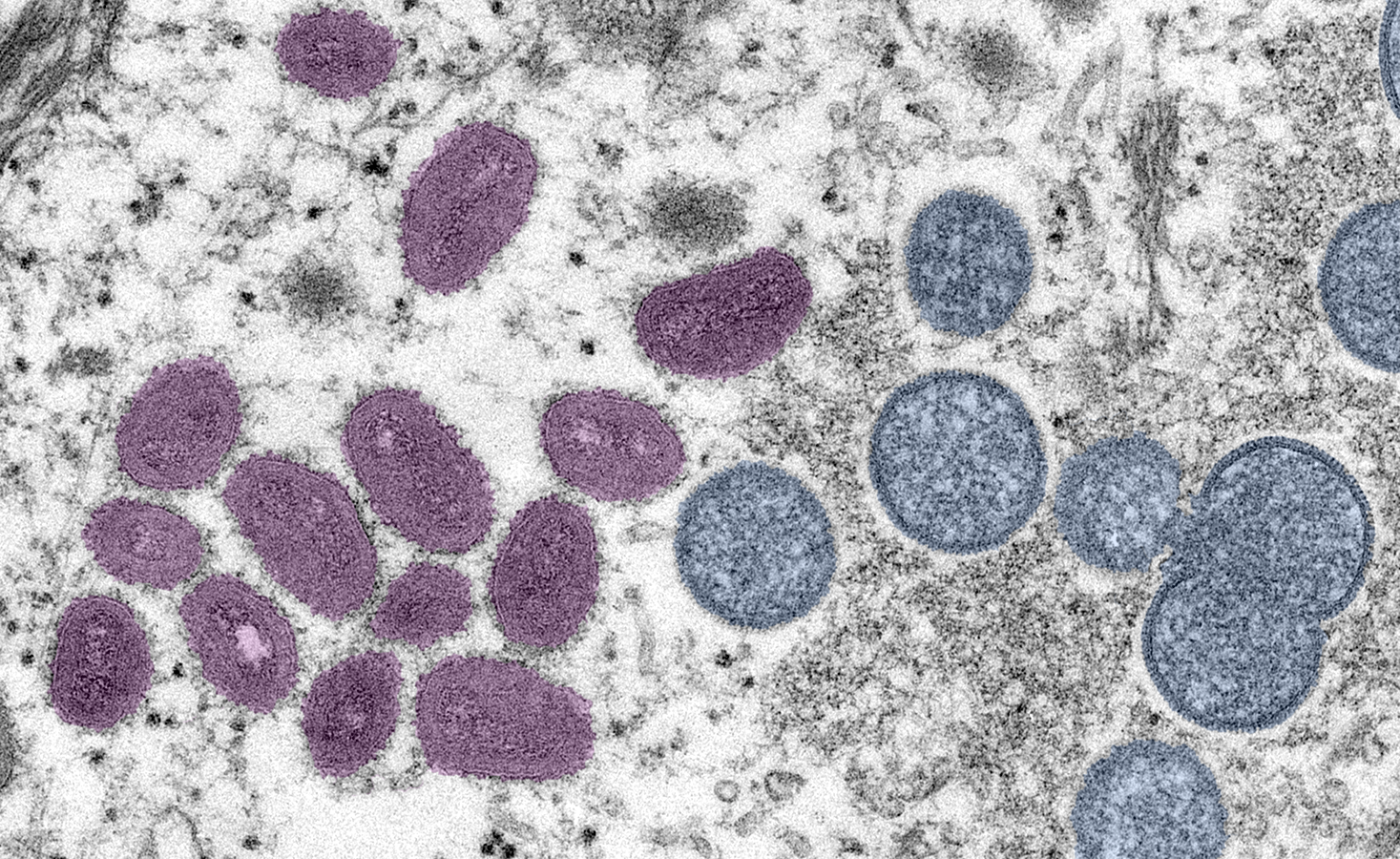

Monkeypox virus particles under a microscope (Image source)

Contact Our Writer – Alysa Salzberg